In the global backpack industry, an interesting phenomenon exists: the true giants never join the debate over “whose backpack is best,” because they stopped competing on the same playing field long ago. Fjällräven sells a Nordic lifestyle; Arc’teryx sells engineering faith; Herschel sells young people’s identity. When we discuss these brands, if we still dwell on product-level details like “fabric waterproofing” or “ergonomic carrying systems,” we miss the real reasons they became giants.

This article attempts, from an industry and B2B perspective, to deconstruct the underlying strategic logic of eight representative companies—how they build moats, how they define categories, and how they establish long-term competitive advantages at the supply-chain and product-development levels.

I. Fjällräven: How does a 40-year-unchanged design keep creating value?

In 1978 Fjällräven launched the Kånken backpack. The original purpose was simple: solve Swedish children’s spinal problems caused by poorly designed schoolbags. Forty-plus years later, the core design is almost unchanged—square body, top twin handles, adjustable shoulder straps, sternum strap. Yet this “old antique” has not been eliminated by the market; it has become a classic product with global sales exceeding several million units.

The logic behind this precisely overturns traditional manufacturing’s “iteration mindset.” Most brands anxiously ask “how to launch new styles every season,” while Fjällräven thinks “how to let one design last 40 years.” The answer lies on three levels:

First, control of the material system. Vinylon F, an improved vinylon fabric, was co-developed by Fjällräven and a Japanese supplier. Its water-resistance, abrasion-resistance, and cold-resistance matter, but more critical is the material’s supply-chain exclusivity, building a technical barrier for the brand. When competitors try to copy Kånken’s appearance, they cannot replicate that unique hand-feel and performance.

Second, clever product-architecture design. Kånken seems to be only one style; in fact, through a size matrix (Mini/Classic/Laptop/Big) and 30+ colorways each season, it creates hundreds of SKUs. The brilliance: highly standardized production lowers unit cost; retail presents rich choice, satisfying consumers’ “collector psychology.” Many Kånken users do not buy one bag—they buy a series in different colors. That is the real value of a long-life-cycle product.

Finally, the most easily overlooked point: Fjällräven’s ability to turn a functional product into a cultural symbol. When a Swedish parent passes a Kånken used in their own school days to their child, the backpack is no longer a “tool for carrying books” but an object bearing family memory and value transmission. This cultural-narrative ability is Fjällräven’s true moat.

For brand owners, the insight is: in today’s fast-fashion dominance, insisting on “slow design” can instead be a competitive advantage. The key is: is your product worth keeping for 40 years? Can your supply chain support such a long-cycle strategy?

II. The North Face vs. Herschel: two completely opposite success paths

If Fjällräven represents “classicism,” then The North Face and Herschel show two different yet equally effective market strategies.

The North Face’s logic is technology spillover. It began as a brand making gear for professional climbers, but what made it a giant was systematically downgrading these professional technologies to the mass market. When you see someone on a city street carrying TNF’s Borealis or Jester commuter pack, they probably will never climb the Himalayas, yet they are willing to pay a premium for the label “professional mountaineering brand.”

The key is layered product-line design. TNF uses the Expedition series (US $300–500) to build professional credibility, the technical hiking series ($150–250) to serve real outdoor enthusiasts, and the daily commuter series ($80–120) to harvest the mass market. Twenty percent of high-end products endorse the entire brand; eighty percent of mid-low products realize sales volume. This “anchoring effect” is efficient: consumers believe that since TNF can make packs that survive extreme environments, daily commuter packs must also be good.

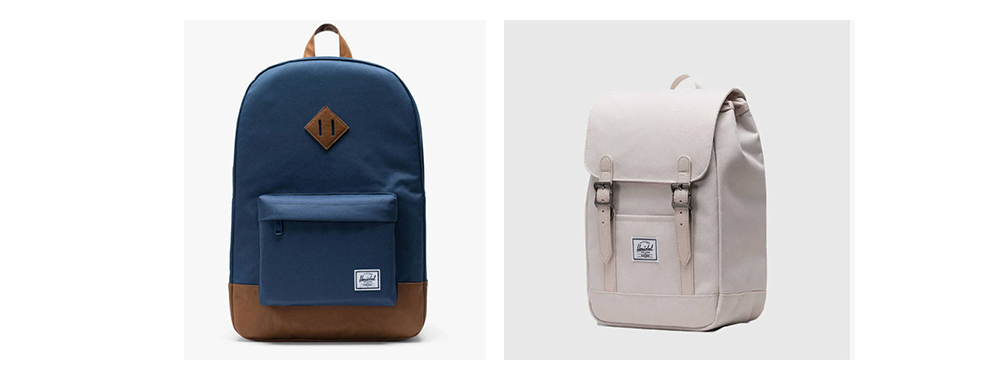

Meanwhile, Herschel proves another possibility with the exact opposite path. Founded in 2009, Herschel has no professional technical accumulation, no outdoor DNA, not even its own factory. Its only core competence: integrate China’s mature bag supply chain to the extreme, then repackage it with visual design and symbolic value.

Herschel’s product structure is highly standardized—core silhouettes number under ten, but through fabric choice, hardware details (signature striped webbing), and print graphics, it launches 50+ new styles each season. From a production view these “new styles” are essentially the same mold with a different skin; to consumers they are “personalized choices.” More importantly, Herschel avoids positioning itself as “functional gear” from the start; instead it places products in lifestyle channels like Urban Outfitters, directly defining them as “fashion accessories.”

Two brands—one from professional to mass, one from fashion to daily—both successfully occupy their markets. It shows one fact: in the backpack industry, product logic and market positioning must match. The North Face can tell a tech story because it has the Expedition series; Herschel does not talk tech because its customers simply do not care about the scientific nature of the carrying system.

III. Patagonia: turning “cost burden” into “competitive advantage”

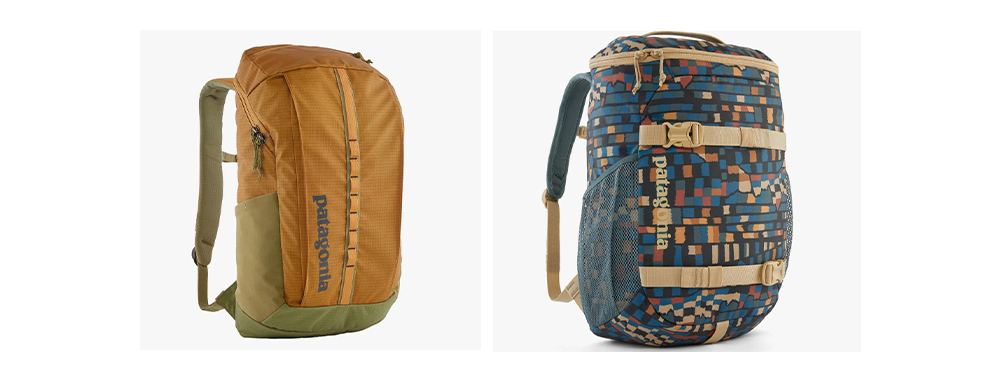

On the surface many Patagonia decisions seem “irrational”: use higher-cost recycled materials, invest in supply-chain transparency systems, offer lifetime repair service, even launch a second-hand trading platform encouraging customers to buy fewer new items. Yet these seemingly “anti-business” decisions let Patagonia build a moat competitors cannot copy.

The key is that Patagonia transforms sustainability from a “moral burden” into “product differentiation.” Take NetPlus® fabric, made from recycled fishing nets, costing 30–40 % more than conventional nylon. Patagonia turns the cost premium into brand premium by telling an “ocean protection” story. Consumers are not paying for “more expensive material” but for “a more valuable choice.”

Smarter is the strategic meaning of supply-chain transparency. Patagonia’s Footprint Chronicles system can trace every product’s raw-material origin, factory, transport path. On the surface this is “social responsibility”; in reality it is a competitive barrier—for competitors unable to reach equal transparency standards, this system becomes an invisible market-entry threshold.

Another overlooked business logic: the relationship between durability and customer lifetime value. A customer who uses a Patagonia pack for ten years and keeps repairing it has an LTV far higher than a consumer who buys a cheap pack every year. The former becomes a brand evangelist, buys other product lines, and forms intense brand loyalty. From this angle Patagonia’s “anti-consumerism” is precisely the shrewdest long-termism.

The industry insight: sustainability is not a cost line; it can be designed as a business advantage—but only if you can, like Patagonia, turn the idea into systematic product and supply-chain capability, not merely a marketing slogan.

IV. Arc’teryx: building a moat with process complexity

In the high-end outdoor-equipment market Arc’teryx is a special existence. Its pack prices are often 2–3× those of competitors, yet large numbers of professional users and high-end consumers are willing to pay. Reason: Arc’teryx proves that in the high-end market, process complexity itself is a moat.

Arc’teryx’s Bora and Acrux series packs extensively use thermo-forming, laser-cutting, seamless bonding. The value of these processes is not to make the pack “more usable” (though it is), but to raise the replication threshold. Even if competitors obtain the same material formula, they can hardly reach equal process levels, because it requires long-term technical accumulation and equipment investment.

Arc’teryx’s decision to keep an owned factory in Vancouver appears special today when OEM is the norm. This factory is not for mass production but for R&D, sampling, and small-batch production. This “R&D + manufacturing” vertical integration gives Arc’teryx extremely fast response in new-tech application—from idea to product can iterate in weeks, not traditional months.

More importantly, through modular design Arc’teryx turns process complexity into supply-chain advantage. Carrying systems, hip-belts, back panels and other core parts are highly modular; on a small SKU base the brand can achieve product differentiation through module combinations. This lowers inventory risk and raises component commonality.

The case tells us: in premium niches pursuing high premium, rather than pouring money into marketing, better build technical barriers in product development and manufacturing processes. Of course this path suits not every brand—it needs long-term investment, deep understanding of target customers, and a financial model able to endure lower volumes.

V. JanSport: the ultimate sample of large-scale standardization

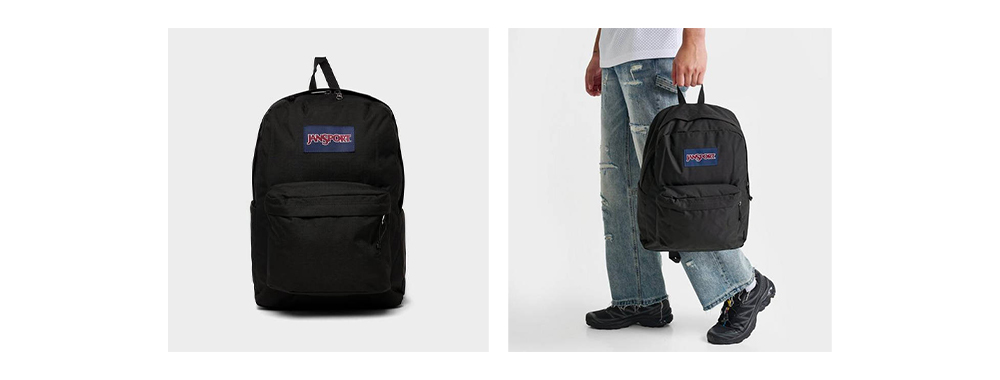

If Arc’teryx represents the “process complexity” path, JanSport is the opposite extreme of “scale efficiency.” Founded in 1967, the brand has long held >30 % share of the North American campus-pack market, relying not on innovation but on pushing standardization to the extreme.

JanSport’s SuperBreak series has barely changed for 40-plus years. This seems “un-progressive”; in reality it is a highly rational strategic choice. When one style’s annual output exceeds 20 million units, any tiny process optimization brings huge cost savings. Industry estimates JanSport’s unit cost is 20–30 % lower than competitors, enough to keep it invincible in price wars.

Smarter, JanSport turns cost disadvantage into a sales tool with “lifetime warranty.” Many think lifetime warranty brings huge after-sale cost; actual data show warranty cost is <2 % of sales. By contrast, the brand-trust and conversion-rate lift brought by lifetime warranty is far higher. In North America JanSport’s brand awareness exceeds 90 %; “lifetime warranty” is one of its core brand assets.

As a VF Corporation brand, JanSport has strong distribution in Walmart, Target, Amazon and other channels. This channel advantage makes it the “default choice”—when a parent walks into a store to buy a schoolbag for a child, the most prominent shelf spot is usually JanSport, reasonably priced, reliable brand, lifetime warranty. In the mass market the value of this “default-choice” effect is often underestimated.

JanSport’s insight is clear: in the mass market, scale itself is the biggest competitive advantage. But the threshold is also high—it needs huge initial investment, mature supply-chain management, and strong channel control. For small-medium brands, rather than head-on competition on this track, better seek differentiated space through niche positioning or DTC models.

VI. Timbuk2: commercial exploration of customization

In a standardization-dominated backpack industry Timbuk2 takes the opposite road: let customers design their own packs. It sounds like a workshop business, yet Timbuk2 proves customization can also be designed as a scalable business model.

Timbuk2’s online customization system lets customers choose size, fabric, color, accessories, combining into thousands of variants. But these choices are based on preset module combinations—customers perceive “infinite possibilities,” while production faces “finite modules.” The brilliance lies in balance: give customers enough freedom to express individuality without letting production run out of control.

More critical is Timbuk2’s “dual-track” production model. Keep a small San Francisco factory for custom orders (3–5 day lead time); build scaled production bases in Vietnam and China for standard styles. This hybrid lets the brand satisfy high-end customers seeking individuality (custom gross margin 65–75 %) while covering the mass market with standards (gross margin 50–60 %).

From a financial view, although custom business accounts for <30 % of volume, it contributes nearly 50 % of profit. More importantly, the brand differentiation brought by custom business lets Timbuk2 build strong competitiveness in DTC channels—why buy on the official site? Because only there can you customize. This moat is hard for pure standard-goods brands to build.

The case shows “customization” and “scalability” are not completely opposed. The key is finding balance: which links can be standardized (module design, production process), which need flexibility (color combination, personalized elements).

VII. Rains: redefining a category

Founded in 2012, Rains became the representative brand of the “urban waterproof pack” category in only ten years. Its success lies not in inventing new technology but in redefining the category itself.

Before Rains, “waterproof pack” basically equaled “outdoor gear”—black or army green, full of rugged outdoor aesthetics. Rains did something simple: move “waterproof” from outdoor to urban scenarios, repackage it with minimalist design language. It created not a better waterproof pack but a new consumer need: a functional-aesthetics product used in city rain.

Rains’s material choice is smart. PU-coated fabric and heat-pressed seamless construction are not high-cost but create a unique visual texture—a rubber-like matte surface highly recognizable among nylon packs. Establishing this “material symbol” is more effective than any ad; when consumers see that texture on the street they instantly identify “that’s Rains.”

Price positioning is also precise: €80–150, sitting in “affordable luxury”—above mass brands, far below professional outdoor brands. This band targets urban middle class: they pursue quality and design, willing to pay premium for “good-looking functional product,” but do not need Arc’teryx-level extreme performance.

Rains’s success proves category-innovation value often exceeds product-innovation value. In a mature market, rather than fight in red ocean, better redefine usage scenario, target group, or aesthetic standard to create a new category. Once you become the category definer you hold pricing power and discourse power.

VIII. Columbia: another possibility of technology populism

Columbia’s position in outdoor gear is awkward: not as technically deep as Arc’teryx, not as belief-driven as Patagonia, yet it remains one of the world’s largest outdoor brands. Columbia’s logic: democratize outdoor technology so more people can afford functional products.

Columbia’s Omni series tech (Omni-Heat thermal, Omni-Tech waterproof) is a classic “good enough” strategy. Performance may not match Gore-Tex or Arc’teryx proprietary tech, but for 90 % of use scenarios it is sufficient, at only half the price of premium brands. The key is Columbia accurately identifies the gap between “professional performance” and “daily need,” and fills that market blank with cost-reduced tech.

| Brand | Price Band | Tech Positioning | Target Market |

| Arc’teryx | $300–600 | Extreme-enviro professional performance | Pro users + high-end consumers |

| Patagonia | $150–300 | Pro performance + sustainability | Eco-conscious + outdoor enthusiasts |

| Columbia | $60–150 | Functional populism | Mass outdoor leisure |

| Herschel | $60–100 | Visual design first | Urban youth |

Columbia’s supply-chain strategy is also pragmatic: build large-scale OEM network in Asia, gain cost advantage through purchase volume, then cover the biggest market with mid-low prices. It does not pursue “the best” but “optimal cost-performance.” In North America Columbia is the first choice for many families—not because it is the most professional, but because it is “good enough and affordable.”

The insight: not every brand must pursue “being the best.” In certain segments, taking mature tech, lowering cost, and spreading it to let more people enjoy functional products is also a valuable market strategy.

Conclusion: the essence of a moat is “non-replicability”

Reviewing these eight companies’ success paths, we find a common point: their moats all point to some kind of “non-replicability.”

Fjällräven’s non-replicability lies in cultural-symbol accumulation—40 years of brand history cannot be speed-grown; Arc’teryx’s non-replicability lies in process barriers requiring long-term tech investment; Patagonia’s non-replicability lies in supply-chain transparency—building a full traceability system takes years; Herschel’s non-replicability lies in supply-chain response speed needing deep cooperation with Chinese factories; Rains’s non-replicability lies in the first-mover advantage of category definer, hard for followers to shake.

These moats share one trait: none are built through a single product or marketing campaign, but through long-term, systematic strategic investment. This also explains why the backpack industry’s Matthew effect is so obvious—once a brand builds a moat, latecomers can hardly disrupt it by “making a better backpack.”

For industry practitioners, the value of these giants is not that their products can be imitated, but that their strategic thinking can be borrowed. In an increasingly crowded market, the real opportunity is not “make a better backpack,” but “find an under-served niche need and occupy it with systematic capability.”

Perhaps the next industry giant is already quietly growing in a segment you haven’t noticed.